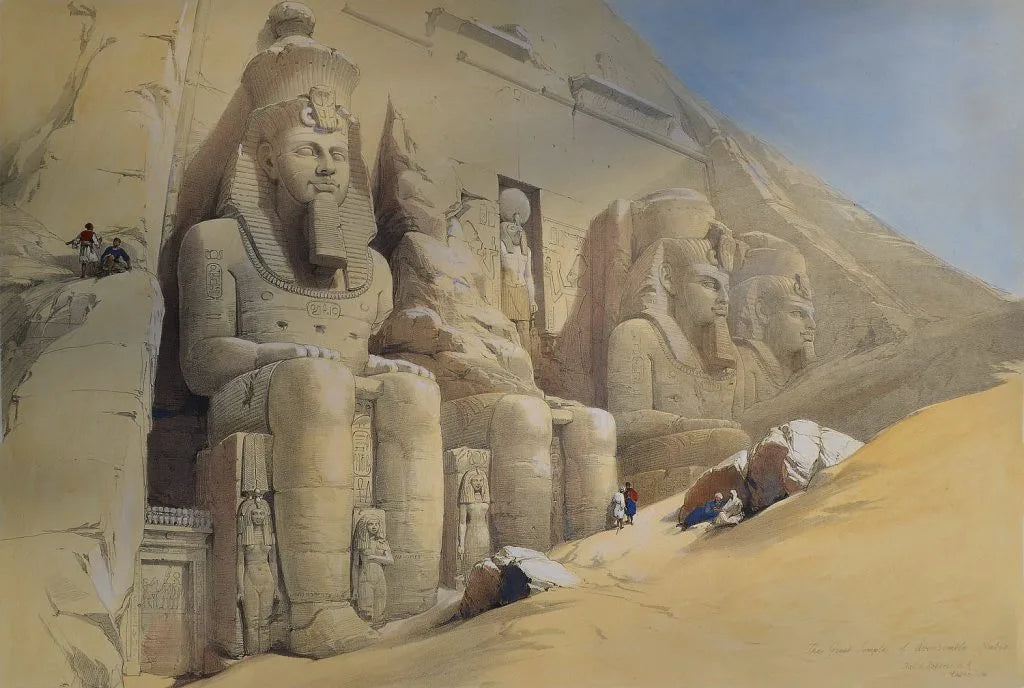

David Roberts RA

Colossal figures in front of Aboo-Simbel

First edition lithograph in stock

Full plate: 133

Presented in a acid free mount

Scroll down for more information about this

The first discovery of this extraordinary Temple was made by the celebrated Jacob Burckhardt on his return from Mahass, after an ineffectual attempt to reach Dongola in the spring of 1813. He had visited the Temple of Isis, the lesser Temple of Aboo-Simbel; and having, as he supposed, seen all the antiquities here, he was about to ascend the sandy side of the mountain by the same path that he had descended, when “having,” he says, “luckily turned more to the southward, I fell in with what is still visible of four immense colossal statues, cut out of the rock, at a distance of about two hundred yards from the lesser Temple: they stand in a deep recess excavated in the mountain; but it is greatly to be regretted that they are now almost entirely buried beneath the sands, which are blown down here in torrents. The entire head and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues are yet above the surface.”

In 1816 Giovanni Belzoni ascended the Nile into Nubia, with the intention of opening the great Temple of Aboo-Simbel, and commenced his undertaking; but the chiefs of the country threw so many obstacles in his way, that at length his funds failed, and he was obliged to discontinue, but not until he had cleared downwards twenty feet in the front of the Temple. It is remarkable that this is the first time the natives learnt the use of money as a recompense for labour.

In the spring of 1817 he returned to his excavations at Aboo-Simbel, accompanied by Mr. Beechy. At Philæ they had the good fortune to be joined by Captains Irby and Mangles, then on their journey in the East. The united exertions of these gentlemen accomplished the entrance to the Great Temple in defiance of the dangers and difficulties thrown in their way, and which are most interestingly narrated in Irby and Mangles’ Travels. Belzoni and his friends removed forty feet of sand, which had accumulated above the top of the door before the recent excavations; but they carried them no farther than three feet below the top of the entrance, when they effected their passage into this Temple, and saw the most extraordinary work that remains to us of the age of Rameses II.

Belzoni describes its facade as one hundred and seventeen feet wide and eighty-six feet high (Wilkinson says, ninety to one hundred feet), the height from the top of the cornice to the top of the door being sixty-six feet six inches, and the height of the door twenty feet. Each of these enormous statues – the largest in Egypt or Nubia, except the Sphinx of the Pyramids – measures from the shoulder to the elbow fifteen feet six inches, the face seven feet, the ears three feet six inches, across the shoulders twenty-five feet four inches. Their height as they sit is about fifty-one feet, not including the caps, which are about fourteen feet. These, the most beautiful colossi yet found in any of the Egyptian ruins, represent Rameses II.; they are seated on thrones attached to the rock.

On the sides, and on the front angles of the thrones, and between the legs of the statues, are sculptured female figures, supposed to be of his wife and children; they are well preserved, though the material is a coarse, friable gritstone. During the execution, defects in the stone were filled and smoothed with stucco, and afterwards painted, of which traces yet remain. The upper part of the second figure has fallen, but the faces of these colossi exhibit a beauty of expression the more striking as it is unlooked for in statues of such dimensions.

Roberts, in his Journal, complains indignantly of the way in which “Cockney tourists and Yankee travellers” have knocked off a toe or a finger of these magnificent statues. “The hand,” he says, “of the finest of them has been destroyed (not an easy matter, since Wilkinson says the forefinger is three feet long) by these contemptible relic-hunters, who have also been led by their vanity to smear their vulgar names on the very foreheads of the Egyptian deities.”